A Long-Term Science-Based Approach

Wildlife researchers look for New England cottontails across the species’ range. They take tissue samples from rabbits found dead after having been hit by cars. They also take samples from rabbits that have been captured alive in special traps. (Afterward, most of these rabbits are released unharmed.)

Some live-trapped individuals are moved to zoos, where they become part of a conservation breeding program aimed at boosting the species' health and numbers. Zoo-bred New England cottontails have been introduced to habitat throughout the species' range.

The scientists also collect rabbit pellets (droppings) in areas of likely habitat, and send them to laboratories, where DNA can be extracted and evaluated to see whether the pellets came from New England cottontails, eastern cottontails, or snowshoe hares, which are also native to the region.

Habitat and Land Ownership Patterns

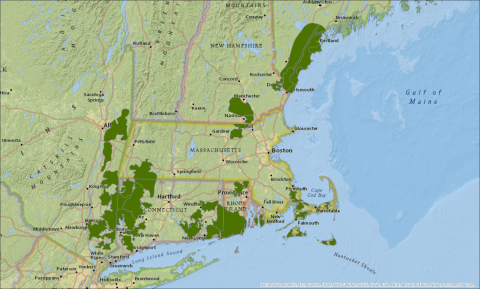

Using data on forest age, shrubland, and the confirmed presence of New England cottontails, as well as land ownership and development patterns, biologists have identified Focus Areas in the six states where populations of New England cottontails remain.

Conservationists concentrate their efforts to protect, create, and renew habitat in those areas.

The recently established Great Thicket National Wildlife Refuge protects young forest and shrubland habitats in New England cottontail Focus Areas. Other wildlife, including ruffed grouse, American woodcock, monarch butterfly, and box turtle also benefit. The U.S. Fish and Service hopes to conserve 15,000 acres across six Northeastern states for the new refuge.

Habitat Projects

Research continues to reveal more information on the best ways to create habitat for this secretive woods rabbit. Habitat projects have been launched on federal wildlife refuges, state wildlife management areas, town and municipal holdings, and land trust properties. Biologists also work with private landowners who want to manage parts of their properties for New England cottontails and other wildlife that need young forest and shrubland. Because most undeveloped land in the region is privately owned, landowners are key to saving and restoring the New England cottontail.